Guide

Essentials

- Installation

- Introduction

- The Kdu Instance

- Template Syntax

- Computed Properties and Watchers

- Class and Style Bindings

- Conditional Rendering

- List Rendering

- Event Handling

- Form Input Bindings

- Components Basics

Components In-Depth

- Component Registration

- Props

- Custom Events

- Slots

- Dynamic & Async Components

- Handling Edge Cases

Transitions & Animation

- Enter/Leave & List Transitions

- State Transitions

Reusability & Composition

- Mixins

- Custom Directives

- Render Functions & JSX

- Plugins

- Filters

Tooling

- Single File Components

- TypeScript Support

- Production Deployment

Scaling Up

- Routing

- State Management

- Server-Side Rendering

- Security

Internals

- Reactivity in Depth

Migrating

- Migration to Kdu 2.7

Meta

- Meet the Team

Render Functions & JSX

Basics

Kdu recommends using templates to build your HTML in the vast majority of cases. There are situations however, where you really need the full programmatic power of JavaScript. That’s where you can use the render function, a closer-to-the-compiler alternative to templates.

Let’s dive into a simple example where a render function would be practical. Say you want to generate anchored headings:

|

For the HTML above, you decide you want this component interface:

|

When you get started with a component that only generates a heading based on the level prop, you quickly arrive at this:

|

|

That template doesn’t feel great. It’s not only verbose, but we’re duplicating <slot></slot> for every heading level and will have to do the same when we add the anchor element.

While templates work great for most components, it’s clear that this isn’t one of them. So let’s try rewriting it with a render function:

|

Much simpler! Sort of. The code is shorter, but also requires greater familiarity with Kdu instance properties. In this case, you have to know that when you pass children without a k-slot directive into a component, like the Hello world! inside of anchored-heading, those children are stored on the component instance at $slots.default. If you haven’t already, it’s recommended to read through the instance properties API before diving into render functions.

Nodes, Trees, and the Virtual DOM

Before we dive into render functions, it’s important to know a little about how browsers work. Take this HTML for example:

|

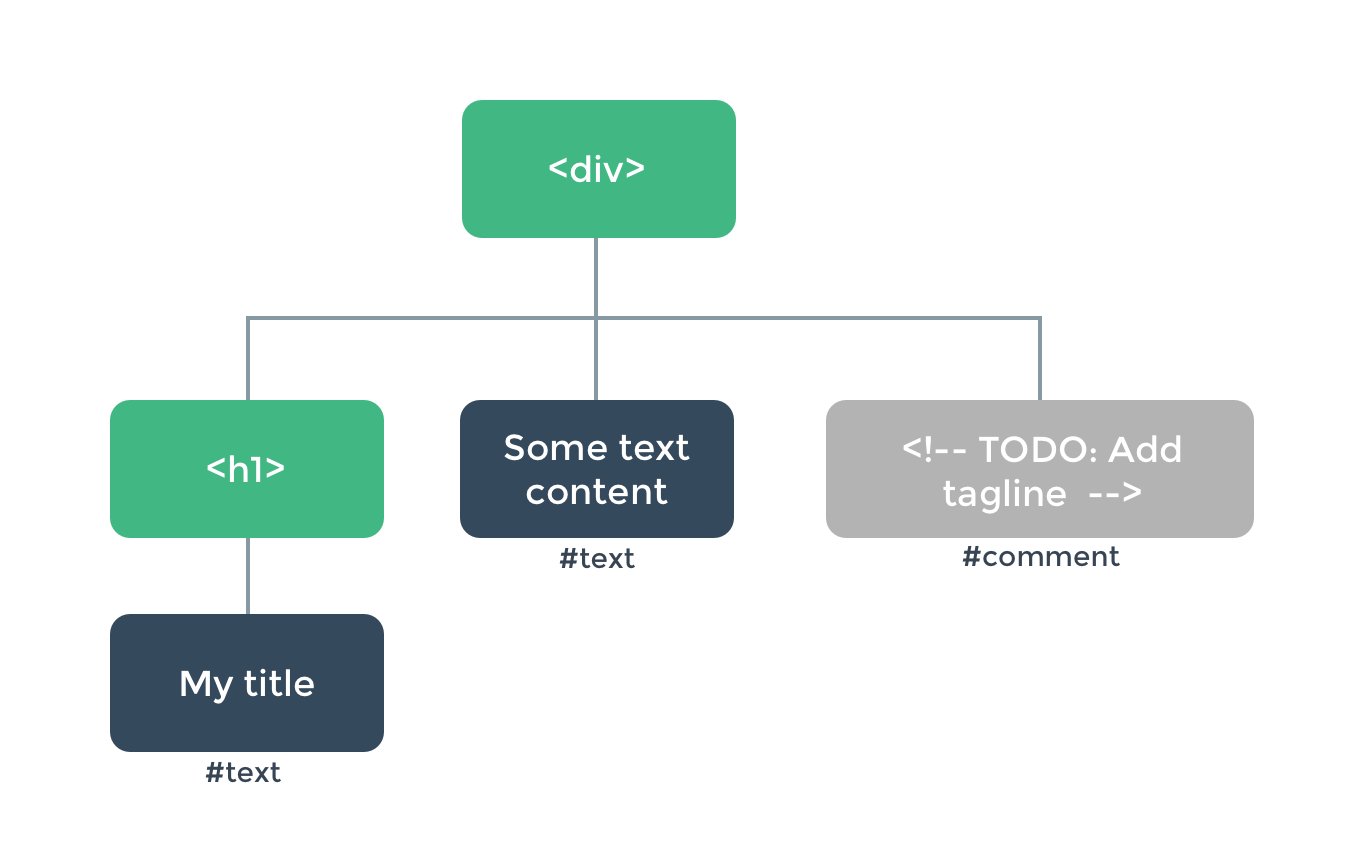

When a browser reads this code, it builds a tree of “DOM nodes” to help it keep track of everything, just as you might build a family tree to keep track of your extended family.

The tree of DOM nodes for the HTML above looks like this:

Every element is a node. Every piece of text is a node. Even comments are nodes! A node is just a piece of the page. And as in a family tree, each node can have children (i.e. each piece can contain other pieces).

Updating all these nodes efficiently can be difficult, but thankfully, you never have to do it manually. Instead, you tell Kdu what HTML you want on the page, in a template:

|

Or a render function:

|

And in both cases, Kdu automatically keeps the page updated, even when blogTitle changes.

The Virtual DOM

Kdu accomplishes this by building a virtual DOM to keep track of the changes it needs to make to the real DOM. Taking a closer look at this line:

|

What is createElement actually returning? It’s not exactly a real DOM element. It could perhaps more accurately be named createNodeDescription, as it contains information describing to Kdu what kind of node it should render on the page, including descriptions of any child nodes. We call this node description a “kdu node”, usually abbreviated to KNode. “Virtual DOM” is what we call the entire tree of KNodes, built by a tree of Kdu components.

createElement Arguments

The next thing you’ll have to become familiar with is how to use template features in the createElement function. Here are the arguments that createElement accepts:

|

The Data Object In-Depth

One thing to note: similar to how k-bind:class and k-bind:style have special treatment in templates, they have their own top-level fields in KNode data objects. This object also allows you to bind normal HTML attributes as well as DOM properties such as innerHTML (this would replace the k-html directive):

|

Complete Example

With this knowledge, we can now finish the component we started:

|

Constraints

KNodes Must Be Unique

All KNodes in the component tree must be unique. That means the following render function is invalid:

|

If you really want to duplicate the same element/component many times, you can do so with a factory function. For example, the following render function is a perfectly valid way of rendering 20 identical paragraphs:

|

Replacing Template Features with Plain JavaScript

k-if and k-for

Wherever something can be easily accomplished in plain JavaScript, Kdu render functions do not provide a proprietary alternative. For example, in a template using k-if and k-for:

|

This could be rewritten with JavaScript’s if/else and map in a render function:

|

k-model

There is no direct k-model counterpart in render functions - you will have to implement the logic yourself:

|

This is the cost of going lower-level, but it also gives you much more control over the interaction details compared to k-model.

Event & Key Modifiers

For the .passive, .capture and .once event modifiers, Kdu offers prefixes that can be used with on:

| Modifier(s) | Prefix |

|---|---|

.passive |

& |

.capture |

! |

.once |

~ |

.capture.once or.once.capture |

~! |

For example:

|

For all other event and key modifiers, no proprietary prefix is necessary, because you can use event methods in the handler:

| Modifier(s) | Equivalent in Handler |

|---|---|

.stop |

event.stopPropagation() |

.prevent |

event.preventDefault() |

.self |

if (event.target !== event.currentTarget) return |

Keys:.enter, .13 |

if (event.keyCode !== 13) return (change 13 to another key code for other key modifiers) |

Modifiers Keys:.ctrl, .alt, .shift, .meta |

if (!event.ctrlKey) return (change ctrlKey to altKey, shiftKey, or metaKey, respectively) |

Here’s an example with all of these modifiers used together:

|

Slots

You can access static slot contents as Arrays of KNodes from this.$slots:

|

And access scoped slots as functions that return KNodes from this.$scopedSlots:

|

To pass scoped slots to a child component using render functions, use the scopedSlots field in KNode data:

|

JSX

If you’re writing a lot of render functions, it might feel painful to write something like this:

|

Especially when the template version is so simple in comparison:

|

That’s why there’s a Babel plugin to use JSX with Kdu, getting us back to a syntax that’s closer to templates:

|

Aliasing createElement to h is a common convention you’ll see in the Kdu ecosystem and is actually required for JSX. Starting with version 3.4.3 of the Babel plugin for Kdu, we automatically inject const h = this.$createElement in any method and getter (not functions or arrow functions), declared in ES2015 syntax that has JSX, so you can drop the (h) parameter. With prior versions of the plugin, your app would throw an error if h was not available in the scope.

Functional Components

The anchored heading component we created earlier is relatively simple. It doesn’t manage any state, watch any state passed to it, and it has no lifecycle methods. Really, it’s only a function with some props.

In cases like this, we can mark components as functional, which means that they’re stateless (no reactive data) and instanceless (no this context). A functional component looks like this:

|

Note: in versions before 2.5.0, the

propsoption is required if you wish to accept props in a functional component. In 2.5.0+ you can omit thepropsoption and all attributes found on the component node will be implicitly extracted as props.The reference will be HTMLElement when used with functional components because they’re stateless and instanceless.

In 2.5.0+, if you are using single-file components, template-based functional components can be declared with:

|

Everything the component needs is passed through context, which is an object containing:

props: An object of the provided propschildren: An array of the KNode childrenslots: A function returning a slots objectscopedSlots: (2.6.0+) An object that exposes passed-in scoped slots. Also exposes normal slots as functions.data: The entire data object, passed to the component as the 2nd argument ofcreateElementparent: A reference to the parent componentlisteners: An object containing parent-registered event listeners. This is an alias todata.oninjections: if using theinjectoption, this will contain resolved injections.

After adding functional: true, updating the render function of our anchored heading component would require adding the context argument, updating this.$slots.default to context.children, then updating this.level to context.props.level.

Since functional components are just functions, they’re much cheaper to render.

They’re also very useful as wrapper components. For example, when you need to:

- Programmatically choose one of several other components to delegate to

- Manipulate children, props, or data before passing them on to a child component

Here’s an example of a smart-list component that delegates to more specific components, depending on the props passed to it:

|

Passing Attributes and Events to Child Elements/Components

On normal components, attributes not defined as props are automatically added to the root element of the component, replacing or intelligently merging with any existing attributes of the same name.

Functional components, however, require you to explicitly define this behavior:

|

By passing context.data as the second argument to createElement, we are passing down any attributes or event listeners used on my-functional-button. It’s so transparent, in fact, that events don’t even require the .native modifier.

If you are using template-based functional components, you will also have to manually add attributes and listeners. Since we have access to the individual context contents, we can use data.attrs to pass along any HTML attributes and listeners (the alias for data.on) to pass along any event listeners.

|

slots() vs children

You may wonder why we need both slots() and children. Wouldn’t slots().default be the same as children? In some cases, yes - but what if you have a functional component with the following children?

|

For this component, children will give you both paragraphs, slots().default will give you only the second, and slots().foo will give you only the first. Having both children and slots() therefore allows you to choose whether this component knows about a slot system or perhaps delegates that responsibility to another component by passing along children.

Template Compilation

You may be interested to know that Kdu’s templates actually compile to render functions. This is an implementation detail you usually don’t need to know about, but if you’d like to see how specific template features are compiled, you may find it interesting. Below is a little demo using Kdu.compile to live-compile a template string: